Several authors have suggested that Nariokotome suffered from growth pathologies that, if corroborated, would preclude the use of this particular skeleton as a reference for Homo erectus skeletal biology (things like maturation rate or stature). Schiess and Haeusler (2013) set out to test whether the skeleton possesses evidence for:

- Unusually small, platyspondylic (that is, flattened) vertebrae.

- Spina bifida, which refers to a series of conditions characterized by the failure of one or more neural arches to close and thus fully encircle the spinal cord.

- Condylus tertius, which is an additional condyle found on the anterior margin of the foramen magnum, right between the two occipital condyles.

- Particularly small spinal canals (spinal stenosis).

- KNM-WT 15000's vertebral heights are more-or-less what you'd expect for his age group (i.e., they are not pathologically flattened relative to modern adolescent humans).

- The skeleton's vertebrae (as measured by superior surface area) do in fact appear to be small.

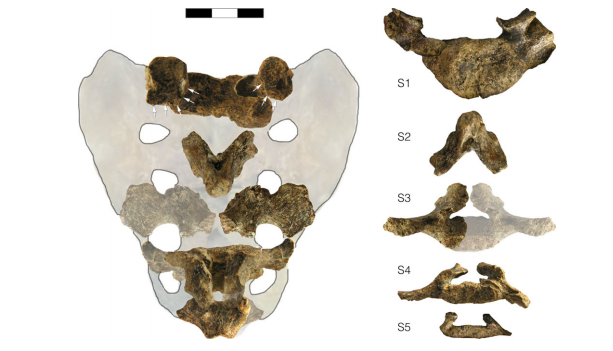

- The non-sacral neural arches that are preserved show no evidence for non-fusion. The 3rd through 5th sacral elements are unfused (see below).

|

| Sacral elements of KNM-WT 15000. From Schiess and Haeusler (2013: Figure 4). |

- A condylus tertius is definitely present.

- KNM-WT-15000's spinal canals are very small compared to the modern reference sample.

[T]he apparent flatness of the vertebrae is typical for the immature age of the Nariokotome boy. There is no indication for spina bifida sensu stricto. An extension of the sacral hiatus from S5 up to S3 is normal in humans of the same age as the Nariokotome boy. The condylus tertius is a developmental anomaly that is relatively common in the normal population unaffected by spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia tarda. It has no clinical relevance. Both the relative smallness of the vertebral bodies and a narrow spinal canal are not classic features of spondyloepiphyseal dyspasia tarda. The criteria for spinal stenosis are met in the cervical, but not in the thoracolumbar region. Moreover, pedicle and canal shape are not typical of congenital spinal stenosis. Rather, a comparison with other fossils suggests that a narrow spinal canal and small vertebrae might be specific to early hominins.It would have been nice to have included individuals with these skeletal abnormalities in the reference sample; surely there is variation in how these conditions manifest (I'm not sure how difficult it is to get a hold of such specimens). Overall, however, they make a convincing case. All of this is not to say that the Nariokotome Boy was perfectly healthy. Schiess and Haeusler do note that the last two lumbar vertebrae are asymmetrical, likely the result of a severely herniated disc, which in turn probably caused a significant limp. Nevertheless, these findings show that the incongruities of the skeletal and dental age-at-death estimates are not the result of a developmental disorder and, further, that this wonderfully complete skeleton can still serve as a useful reference for Homo erectus skeletal biology.

References:

Graves, RR, Lupo, AC, McCarthy, RC, Wescott, DJ, Cunningham, DL (2010). Just how strapping was KNM-WT 15000? Journal of Human Evolution 59, 542-554.

Schiess, R, Haeusler, M (2013). No skeletal dysplasia in the Nariokotome Boy KNM-WT 15000 (Homo erectus) - A reassessment of congential pathologies of the vertebral column. American Journal of Physical Anthropology 150, 367-374.

No comments:

Post a Comment