I actually was not aware of its publication until I came across it on John Hawks's

weblog, but Joseph Ferraro and his coworkers have come out with a detailed taphonomic analysis of the faunal remains from Kanjera South, an important Oldowan site from Kenya that dates to about 2 million years ago. Their abstract does a nice job of summarizing the significance of the site and the study's findings (I guess this is what abstracts are supposed to do, after all; Ferraro et al., 2013: 1):

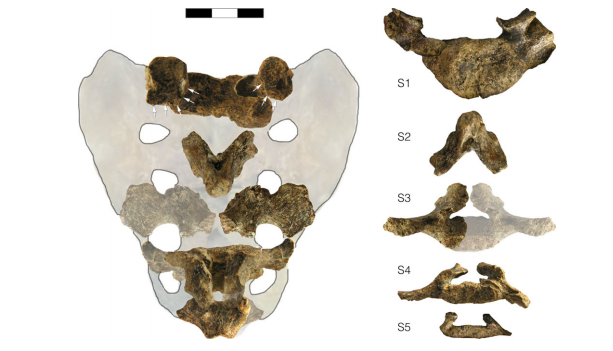

The emergence of lithic technology by ~2.6 million years ago (Ma) is often interpreted as a correlate of increasingly recurrent hominin acquisition and consumption of animal remains. Associated faunal evidence, however, is poorly preserved prior to ~1.8 Ma, limiting our understanding of early archaeological (Oldowan) hominin carnivory. Here, we detail three large well-preserved zooarchaeological assemblages from Kanjera South, Kenya. The assemblages date to ~2.0 Ma, pre-dating all previously published archaeofaunas of appreciable size. At Kanjera, there is clear evidence that Oldowan hominins acquired and processed numerous, relatively complete, small ungulate carcasses. Moreover, they had at least occasional access to the fleshed remains of larger, wildebeest-sized animals. The overall record of hominin activities is consistent throughout the stratified sequence - spanning hundreds to thousands of years - and provides the earliest archaeological evidence of sustained hominin involvement with fleshed animal remains (i.e., persistent carnivory), a foraging adaptation central to many models of hominin evolution.

This research team has been working hard out a Kanjera for many years now, and its really nice to see a comprehensive analysis of the faunal material from the site (we'd been getting tantalizing hints in various publications and presentations for some time).

Before we proceed, let me summarize the state of affairs just prior to these latest data. The 1.8 Ma time marker that Ferraro et al. mentions refers to the burst of evidence for meat-eating that emerges almost exclusively from Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania. One site in particular, the very well-known Level 22 at the gorge's FLK locality (also known as the

Zinjanthropus Floor), dates to about 1.84 Ma and preserves thousands of fossils, many of which bear clear indications of hominin butchery. Now, up until a few years ago, it was thought that the animal bones from many of the other sites from Beds I and II of the gorge (ca. 1.9-1.2 Ma) were also largely the result of hominin activity. However, my colleagues and I showed that there are really only two sites, the previously mentioned FLK 22 from Bed I, and the site of BK, in upper Bed II (about 1.3 Ma), that are largely the result of hominin butchery (Domínguez-Rodrigo et al., 2007, 2009; Egeland, 2008; Egeland and Domínguez-Rodrigo, 2008). Now, we're not saying that hominins weren't at the sites; they certainly made, used, and left stone tools at these locations, but they were not doing a lot of meat-eating. There are a couple of other Oldowan sites here and there with some evidence for butchery, but if we ignore FLK 22 for the moment, good evidence for lots of meat-eating (or, to use Ferraro et al.'s term, "persistent carnivory") really doesn't pick up until

much later, perhaps about 1.5 Ma.

What does all of this have to do with expensive tissues? Well, researchers have come up with several well reasoned, and very popular, human evolutionary models based ultimately on the shift to meat-eating. To start, brains and guts are very expensive tissues: one does a lot of thinking and the other does a lot of digesting, both of which take up good amounts of energy. If you start eating more meat, which is nutrient dense and easy to digest, you can divert energy from the guts to develop bigger noggins. Other possible correlates of a diet based increasingly on meat would be increased range size (carnivores, and other animal that eat high quality, easy to digest foods, tend to have larger ranges) and unique life histories (extracting nutrients using technology, and hunting with technology in particular, are difficult things to learn, and you don't want to die before you learn how to do them well, so perhaps we've evolved extended life spans to fit this need). People have traditionally seen the evolution of

Homo erectus, with its bigger brain, long, lanky legs, and ability to leave Africa to colonize parts of Eurasia, around 1.8 Ma as great evidence for these shifts. Ok, all well and good, but, to use an old phrase: where's the beef? In other words, where is the evidence for sustained meat-eating just before and as

H. erectus was evolving? Other than a single site, FLK 22, there really wasn't much...until now.

This is what makes the Kanjera evidence so important. I'm not sure it completely quashes my reservations (after all, we still only have two sites with good evidence for regular meat-eating between 2.6 Ma, when stone tools were first invented and used to butcher carcasses, and 1.5 Ma), but it is a good start.

References:

Domínguez-Rodrigo, M, Barba, R, Egeland, CP (2007). Deconstructing Olduvai: A taphonomic study of the Bed I sites. Springer, New York.

Domínguez-Rodrigo, M, Mabulla, AZ, Bunn, HT, Barba, R, Diez-Martín, F, Egeland, CP, Egeland, AG, Yravedra, J, Sánchez, P (2009). Unraveling hominin behavior at another anthropogenic site from Olduvai Gorge (Tanzania): New archaeological and taphonomic research at BK, Upper Bed II. Journal of Human Evolution 57, 260-283.

Egeland, CP, Domínguez-Rodrigo, M (2008). Taphonomic perspectives on hominid site use and foraging strategies during Bed II times at Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania. Journal of Human Evolution 55, 1031-1052.

Ferraro, JV, Plummer, TW, Pobiner, BL, Oliver, JS, Bishop, LC, Braun, DR, Ditchfield, PW, Seaman III, JW, Binetti, KM, Seaman Jr, JW, Hertel, F, Potts, R (2013). Earliest archaeological evidence of persistent hominin carnivory. PLoS ONE 8, e62174.